Some thoughts on…

Glass Bees by Ernst Junger (1957)

Andromeda by Ivan Yefremov (1957)

Solaris by Stanislaw Lem (1961)

The Dispossessed by Ursula K. LeGuin (1974)

Some thoughts on…

Glass Bees by Ernst Junger (1957)

Andromeda by Ivan Yefremov (1957)

Solaris by Stanislaw Lem (1961)

The Dispossessed by Ursula K. LeGuin (1974)

“’Excess is excrement,’ Odo wrote in the Analogy. ‘Excrement retained in the body is a poison.’

Abbenay was poisonless: a bare city, bright, the colors light and hard, the air pure. It was quiet. You could see it all, laid out as plain as spilt salt.

Nothing was hidden.” (Le Guin 98)

Shevek’s time in Abbenay constitutes the most formative period of his life, acts as a kind of college experience for him. Here, doing work for Sabul, Shevek really is forced to finally grow up. Though always enjoying solitude, Shevek from Chapter 2 shows a kind of optimism that simply is no longer present in Shevek from Chapter 4. Whereas an 18 year old Shevek feels thwarted in being held back from pursuing physics, a 20 year old Shevek is now realizing that what really is holding him back is himself, as well as his society. Shevek realizes that Sabul’s career is built off of dominating others and then profiting off of their successes, and in meeting his mother, Rulag, a doctor at the clinic he goes to when he falls ill, realizes that she, too, is trying to profit off of him. She left parental affection to Palat, Shevek’s father, who died when he was only 12. Left alone to think in his own room for the first time ever, Shevek realizes a truth that he is truly dangerous to the security of a society built on interdependency: he doesn’t need anyone else. He is happiest alone with his room working on physics because no one around him is his intellectual equal; his equals are far away, in a place forbidden and forsaken, only accessible through servitude to Sabul. In a society built upon the throwing off of rank and hierarchy, Shevek comes to realize that disparity, whether it be of intelligence or of emotion,is integral to human nature, and hierarchy always forms, even if unspoken. He realizes that Abbenay isn’t “poisonless” at all; Abbenay makes him physically ill, and for the first time in his life since the prison experiment of his childhood, truly questioning the validity of the society he has been led to believe is the epitome of what one could hope for. Shevek realizes, in the city which forms the central cog in the machine of Annares, that maybe no machine can be perfect. Quite a lot, in fact, is hidden in Abbenay, and perhaps Shevek will only be able to truly think that through if he steps back from it.

__________________________________________________________________________

For this blog post, I want you to draw on the SF theory that we have read in order to discuss how Le Guin’s novel uses the possibilities of SF or utopian literature in order to offer a social critique.

Science fiction, at its core, is always engaging with one central question: what does it mean to be human? Often, this is accomplished through the estrangement of our own society (cognitive estrangement, as Suvin calls it) so as to view it more critically, and/or the use of the extraterrestrial to compare or contrast with humanity. Le Guin approaches this critical, existential question of what we owe to each other and to ourselves through the framework of a world of twin utopias, anarchy and archy, different in every way, both viewing themselves as perfect, both deeply flawed. Though it has been posited by numerous SF scholars that traditional literary criticism cannot effectively be applied to science fiction, as it developed outside of the Western literary tradition, I personally feel there is one thing that reinforces what hopeful alternative is offered amongst the criticism of the status quo in The Dispossessed; classic literary theory posits that there are only two kinds of stories: a hero goes on a journey, and a stranger comes to town – and that they are, in fact, the same story, only differing in perspective. In building a story centered around the building and unbuilding of walls, a world where the grass is greener on both sides depending on your point of view, Le Guin has engaged this theory. In the world of Le Guin’s dueling utopias and in our reality, while there appears to be only black and white, there is always gray. Where there is evil, there are always good; unfortunately, the inverse is also true. Shevek, through leaving Anarres and coming to Urras, learns that history is always cyclical – again, a group of revolutionaries, his brothers and sisters, dare to question the order of things, to dream of a world where all are equal – Shevek’s own world. And yet, Shevek came to this world to seek clarity regarding the flaws of his own world: how on a world organized around justice and equality, around the grounding principle of mutual aid, the human wickedness of injustice and power remains. Le Guin offers us the idea that utopia is both impossible and possible, past and present, and masterfully frames this through the lens of science in the way of Shevek’s theoretical physics, sequency and simultaneity, time and space. There is no universal truth, no objectivity; there is only what there is. And that’s okay. In a world that demands purpose, knowledge for the sake of its acquisition is still worthy.

__________________________________________________________________________

Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed is a novel firmly rooted in the question of what we as individuals owe to both ourselves and to each other, so it felt natural to include my classmate Vinh Nguyen’s ideas about the text alongside my own. I really like Vinh’s application of some of Samuel Delany’s, another giant of the genre, ideas about writing to Le Guin’s text; Vinh’s analysis of the implication of the diction of the novel’s opening is lovely.

“Le Guin’s The Dispossessed is an excellent example of Samuel Delany’s theory of writing being a constant reimagining of an image caused by every proceeding word. Science fiction is when the author forces the reader beyond our personal experience with “violent leaps of imagery” (Delany 12). The subjunctivity of the novel is defined by the images created by the words used. The beginning of the novel encapsulates this idea perfectly. It starts with “THERE was a wall. It did not look important” (Le Guin 1). The most basic of explanations given for our entry to the novel. Not much of an attention grabbing image, but Le Guin continues to build on it. She explains how this wall can be easily climbed over. The power of the wall comes from the mental boundary. This still doesn’t sound out of this world yet. We have borders of nations and property lines that are similar enough to this. The sentence is what brings us into the realm of science fiction. “For seven generations there had been nothing in the world more important than that wall” (Le Guin 1). There hasn’t been anything in human history that is similar to a border defining a society’s existence. The closest comparison is West Berlin and the Berlin Wall, however this was forced upon the people of Germany as a result of the Cold War. Later on in the novel, we will learn that the people of Urras adore the wall and the isolation it brings them. This wall allows Le Guin to explore the idea of humanity embracing isolationism as its core tenant on a planetary scale, and how they would interact with humans from different planets. The image of a small wall being a defining characteristic of an entire planet of humans makes the reader question why is the wall so important, why was it built, how has it affected human society, etc. The imagery and the importance of the image that Le Guin starts the novel with forces us to explore the possibilities of this image. The second paragraph also explains that “all walls [are] ambiguous, two-faced” and are defined by “which side of it you were on” (Le Guin 1). This now brings the images of what is outside and questions of how the wall affects both sides.”

In what ways is this novel about “the limits of human cognition”? What does it suggest, so far, about the possibility of recognizing alien life? Choose one short passage (1–4 sentences) in the novel’s first nine chapters and use it as a basis for exploring these questions.

“We don’t need other worlds. We need mirrors. We don’t know what to do with other worlds. One world is enough, even there we feel stifled. We desire to find our own idealized image; they’re supposed to be globes, civilizations more perfect than ours; in other worlds we expect to find the image of our own primitive past.” [Lem, Stanislaw. Solaris (p. 58). Pro Auctore Wojciech Zemek. Kindle Edition.]

As this passage suggests, the “limits of human cognition” are, paradoxically, human cognition itself. We can only truly grasp and understand that which makes sense to us; generally, that which makes sense to us is only that with which we have at least some kind of analogous basis of comparison. In expanding the limits of what we know, in science, in math, we are never truly searching for an answer, per se. We are searching for affirmation. We want to see that others, on Earth or in another galaxy, have done what we have done or will do what we have done or have done what we hope to do. As Lem points out, our search is for sameness, our cognition’s limit is familiarity, because that is what is comforting; as Solaris shows, discomfort and lack of understanding is what leads to insanity. Humanity’s fascination with the idea of not just extraterrestrial life, but extraterrestrial life that is humanoid in some way, stems from that same vain desire that drives human cognition – we are terrified of and unable to reconcile with the idea of a universe in which we are completely and utterly alone. Kelvin, by the end of this section of the novel, has fallen in love with and is holding tight to this humanoid representation of his long dead wife; he says himself that she isn’t really even necessarily a faithful replica of his wife as she was, for if she were, he might not love her as he does. When he was obsessed with knowing just what this “creature,” Harey, was, he was disgusted and terrified. Once he abandoned the scientific drive for knowledge, he loved her. Why? Because that was what he already knew. He loved his wife in life. And now, as unconventional and unnatural as this Harey 2.0, who makes a point to distinguish that she is NOT the original, he knows that he loves her. This is why he is saner and more content than Snaut or Sartorius; he is not attempting to surpass the bounds of human cognition, as they are attempting to do, because he knows that the “thinking without consciousness” of the ocean is something that we, as humans, could never understand.

__________________________________________________________________________

Pick one sequence/scene from Tarkovsky’s Solaris. For our purposes, we can define a sequence as a continuous part of the film that takes place in one setting. Your sequence should be at least 3 minutes and at most 10 minutes long. Rewatch your chosen sequence at least two times. Take careful notes while doing so: what do you notice? What is this sequence doing, in terms of cinematography, editing, mise-en-scène, and sound? (You can find the definitions of these terms on myCourses, under “Handouts” and “Slides.”) Write your blog post about your chosen sequence. You may address any aspect of it you like, but your post must include at least three formal details—things that you noticed while taking notes on the four categories mentioned above. If you need a more specific prompt to get your ideas flowing, then consider how your chosen sequence adapts, responds to, or modifies the relevant passage from Lem’s novel. What similarities, what differences do you notice between the film and the novel (again, only in terms of your chosen sequence)?

(Sequence: 00:33:30 – 00:38:24) This sequence, almost like a “guest” would in the world of Solaris, haunted me. As I rewatched it again and again for analysis, I found myself getting increasingly angry over the artistic choice to include five whole minutes of nearly silent highway footage in a movie about outer-space exploration. The only conclusion I could come to was this: scale. This sequence’s editing features back and forth inter-splicing of close-up shots of Burton (and at times, the unnamed child, who from context we can assume is Fechner’s orphaned son), first person point-of-view shots of looking at the traffic through the windshield of the car, and wide-angle overviews of the crowded highway. I think these play into my idea of this sequence establishing scale. Burton is one man, a man deeply disturbed and tortured by both what he saw on Solaris and the fact that few believe him, in a huge world. Lem, in the source text of this story, wanted to make clear that we as humans are so individualistic that we very rarely can grasp the broad. How are we to suppose that we can understand, let alone communicate with, a being so huge it spans an entire planet, when each and every day we pass thousands, if not millions of our peers, without ever acknowledging the sheer scale of humanity at large? I think this sequence is also one of the most nerve-wracking in the film, largely due to the sound, or lack thereof. Diegetically, we hear only the ambiance of the highway, fairly stock standard sounds of wheels on pavement and the gusts of wind from vehicles passing each other at high speeds. Non-diegetically though, at around the 36-minute mark, the volume slowly builds on some unintelligible background noise, something almost alien. It creates a deeply unsettling mood, and made me feel almost as on-edge as I did while reading the novel. The only way I can think to describe this sound is as a distorted whale song, but in any case, it brings to mind something not human and creates tension. Lastly, the cinematography of this sequence struck me in the way that the film continuously oscillates between being in black and white and being in color. Burton, however, is always in black and white. I think this speaks to an important theme carrying over from the novel: the limits of human cognition. We seek to understand the motivations and machinations of a vast, sentient, plasmic entity, and yet we cannot understand ourselves. I think the black and white serves as a visual indicator of this confusion and unclear-ness; while the background shots of cars and roads are completely intelligible, Burton (and the boy) are more difficult to read. Overall, though this scene was added to the film and does not originate from the source material, I think this sequence more accurately captures the intentions and mood of Lem’s novel than any other part of the film.

__________________________________________________________________________

In analyzing Tarkovsky’s film adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s novel Solaris, my classmate Masato Hirakata chose to write about the same sequence that I did: a 5 minute or so long sequence in which there is no dialogue, nothing really happens, and most of the footage is of cars on a highway. I have admired Masato’s ideas all semester long, and I think this post really highlights his outside-of-the-box thinking. I appreciate how despite choosing the same seemingly meaningless segment of the film, we were both able to imbue through our analysis two very distinct and interesting meanings.

“Sequence 32:17 – 38:23

When I was watching this sequence, I was surprised to see that the highway Henri Burton is driving on is in Japan. At 33:33, you can see the sign above the tunnel that says “Akasaka Tunnel,” both in Japanese and English. The very skyline itself evoked an intense feeling of nostalgia in me, especially at around 34:34, where the camera drives past a stone wall along a river. Russia and Japan are more deeply involved with one another than most people realize, and I feel that their complex relationship is demonstrated here through the highway sequence in a very interesting manner. In the Russian Far East, there is a large number of right hand drive vehicles due to the import of used cars from Japan, which is a left hand traffic country. Territory disputes continue to the present day, and the Japanese victory over the Russian Empire in the Russo-Japanese War threatened the supremacy of the white man, while bolstering Japanese confidence in themselves.

Despite this fraught relationship, movies like Solaris and The Silent Star seem to make it a point to include a Japanese presence. Geographically, Japan was well within the sphere of influence of the Communist and Soclalist powers, chiefly the USSR and the PRC. This is precisely what made Japan so important in the American foreign policy, alongside countries like the Philippines, to safeguard the Far East against a Communist domino effect. For media like Solaris and The Silent Star to include Japan so casually within the narrative acts as a statement, specifically in the context of scientific innovation and space exploration. In the face of grand human progress, political machinations fall by the wayside as socialism paves the way for greatness, no matter Capitalism and the United States’ best efforts.

In the context of the movie, the sequence is critical due to its usage of color. Immediately prior to the sequence, the movie is in color, while the program on the Solaris station is shown in black and white. Burton’s video call is also in black and white, paralleling his younger self in the archived footage giving a report on Fechner’s disappearance and the appearance of a four meter tall construct of Fechner’s son. Now shown in black and white where he had formerly been shown in color, Burton is both physically and figuratively removed from the reality that was the house. Despite technically being in the same time temporally as Kelvin and his parents, Burton is now turning into a memory, losing detail and focus.

The setting itself is also important to note. Burton is calling from the city, and is driving along a highway, which twists and turns along the artificial: the buildings, tunnels, and the highways. Meanwhile, Kelvin and his parents remain in the house, which is a “natural” reality of a lake, grass, trees, and an open sky, and remain shown in color. However, towards the end of the highway sequence, the highway begins to regain color, as the city turns to night, and the city “comes alive.” In direct contrast to this, as the highway sequence ends, it is the house, Kelvin, and his parents that are now shown in black and white. Kelvin is burning his papers from the past, and getting rid of the ties that bind him to his parents’ house, which itself is said to be built to resemble the house of Kelvin’s great grandfather. As Kelvin is set to head to the Solaris Station, an “artificial” reality, the movie shows us the shifting state of memory and reality, as Burton, Kelvin’s parents, and the natural house fades away, as Kelvin’s reality on Solaris and the artificial station becomes the reality.”

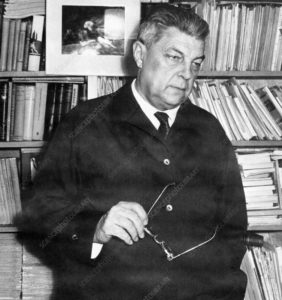

Ivan Antonovich Yefremov (1907-1972), Soviet palaeontologist and science fiction author. Yefremov founded the science of taphonomy, the study of the fate of dead organisms in the geosphere and biosphere. He won the USSR State Prize for this work. His most famous novel was ^IAndromeda Nebula^i (1957). Photographed in 1968, in Russia.

On pages 77–78 in the novel there are two paragraphs in which Darr Veter considers a dinosaur skeleton. Why is this passage significant? Interpret this passage by analyzing what you feel are important details in the text, and by contextualizing the passage within what you now know about Soviet culture, Socialist Realism, or science fiction.

[Response to Andromeda Prompt 3, re: dinosaur skeleton] As Csicsery-Ronay discusses in “SF and the Thaw,” the Thaw and the campaign against socialist realism that followed allowed room in literature for the presence of “sincerity” and personality and the introduction of personal hope through the humanizing (and by extension, personalizing) of science. The significance of a passage in Andromeda to me is that Yefremov, apart from being a writer, was himself a paleontologist. The presence of a relic of Yefremov’s work is a making personal of science, and the in-depth description of the bones in the text shows clear signs of a kind of real appreciation. Despite the many aspects of Andromeda which do align with socialist realist sf, i.e. didacticism, collective protagonists, emphasis on science and materialism, this one passage is especially interesting because it violates socialist realism’s cardinal rule: it discusses history. It dares to mention that precious man, in its glorious humanity, evolved from “clumsy, heavy” creatures (Yefremov 77). Though the Soviet New Man, as discussed in the Gomel reading, is something that was largely developed following the publication and widespread success of Andromeda, socialist realism did still place an emphasis on the idealization of humanity, and so it is shocking and interesting that Yefremov would include this. To include at all, let alone emphasize, the existence and sentience of a living creature that is non-human is incredibly anomalous in this period. It makes sense then to me how Thaw sf is classified as the middle zone between opposition and conformity, and why Andromeda is viewed as the founding text of this period – this passage embodies that. Yefremov, in writing a stereotypical socialist realist text but sprinkling in just a hint of something personal, a small callback to history, is tiptoeing the line of what is accepted and what is forbidden. This novel is a strange kind of paradox, a marriage of things that don’t quite match, much like the Soviet New Man. Andromeda celebrates man’s achievements and the immortality of knowledge, yet highlights the inherent danger of man’s Icarus complex in relation to science, and the kind of existential futility that comes with mortality. It has the timeless-present (rooted in the temporal unknown) quality of socialist realism, yet makes allusion to real history, almost laughing in the face of the state’s conventions. Immediately after the discussion of dinosaurs, Yefremov is smart to relate it to the biological superiority of Veda, linking the evolution over time as a kind of natural eugenics. This passage toes an important line, exists in a transitory period of Soviet history, and embodies as a whole how the novel too exists in that period.

(Group 6: Julian, Tony, Devin, Vinh, Paige. Passage: pp. 86–88, from “I had always believed that Zapparoni’s monopolies” to “His voice was pleasant, by the way” (ch. 7).) What does this passage tell us about the narrator? What do you notice about the language of this passage? How do its structure, style, and word choice affect its meaning? How would you characterize the mood or the tone of this passage? Why? How does this passage depict technological change? historical change? social change? In what sense could this passage be considered part of a work of science fiction? Does the narrator use any words, phrases, or make any references that you needed to look up in order to understand? Does the narrator use any metaphors or other figurative language in this passage? To what effect? What connections would you want to make between this passage and the rest of the novel so far?

I personally took a special interest in the line, “’Once again and year by year—‘: on this note the catalogue of the Zapparoni Works was tuned, a book which was looked forward to every October with an eagerness never enjoyed by any fairy tale or utopian novel” (Jünger 87). There’s something immediately fourth-wall breaking, almost eerie even, about the mention of utopian novels within a text in which you are deeply diving in search of sf connections. Out of all of the genres and analogies that Jünger could have chosen, he selected to highlight fairy tales and utopia. Why? This question, which I ask myself, I’m not sure I have the answer to just yet. I think it has something to do with fairy tale and utopia essentially being opposite sides of the same coin – both strive for the idea of perfection, but what is fantastical and one is rooted in science – and this is much the impression we get of the Victor Frankenstein and Santa Claus hybrid that is Zapparoni. I find this line to be a very succinct and accurate summary of the sense of Zapparoni we are given in this first half of the novel. He strikes me as a kind of marriage between the old world and the future; he is reminiscent of the past which is yearned for and revisited frequently by Richard in character, appearance, and especially in the description of his almost Victorian English estate, and yet he is the architect of the future of this world. Zapparoni, and the world he lives in, is the embodiment of juxtaposition. He lives in an almost Journey to the Center of the Earth-esque pastoral paradise located beneath a gray, uniform, mechanical factory of autonomous production. Zapparoni is simultaneous warm and welcoming to Richard, while also very cold and calculated in his assessment of him, underneath the Santa Claus façade. This passage is the embodiment of all of that – the children of the world, representative of the future, the next generation, eagerly wait with child-like wonder to be consumed by the cold, robotic, capitalist overlord. The title of the novel, deriving its name from the autonomous creations living in Zapparoni’s garden, which we meet towards the end of our assigned reading section, again draw a parallel with their creator; Zapparoni himself is a glass bee, something beautiful and pure and working for the greater good in theory, but transparent, industrious, and invoking a feeling of the uncanny in practice.

________________________________________________________________________

For our class discussion of Glass Bees by Ernst Jünger, my classmate Tony Lukin and I were assigned the same passage to close read. Collaboration, like in the genre’s most famous plots, has been indispensable to the acquisition of knowledge in this class, and so I felt it vital to include Tony’s post alongside mine — both for the sake of comparing and contrasting our ideas, and as a representation of the great discussion we had about our ideas in the class following the writing of these blog posts. I especially admire the way Tony emphasizes how in the novel, we only ever see things through the perspective of Richard, and what the implications of this may be to our comprehension of the text.

“This passage from “The Glass Bees” conveys Richard’s emotions felt toward Zapparoni when he is introduced to the inventor for the first time. Giacomo Zapparoni is one of the most prominent and wealthy figures of the time who runs a large firm that builds advanced robots. The character of Zapparoni is labeled as very cryptic and elusive throughout the book, so for Richard to be able to meet Zapparoni in-person shows him the differences between the public and the private persona of the entrepreneur. The passage clearly expresses that Richard was in a state of shock and awe when he initially saw Zapparoni. The public image of Zapparoni that was created through films described him as “a benign grandfather or a Santa Claus”, but Richard stated that “the great Zapparoni…did not in the least resemble the person who I was facing” (86). This creates an interesting question of who Zapparoni might actually be if the public descriptions of his appearance do not match his actual appearance. The language that is used in this passage carries a very respectful and somewhat curious tone as Richard continues to further express the vast admiration that he holds for Zapparoni, despite the differences in perceived appearance, since he simply described him as “great”, “skillful”, or someone that has a “mercurial intelligence”. Even though Richard was surprised by Zapparoni’s actual appearance compared to his perceived image of him, Richard did not lose any of the respect or admiration that he had towards Zapparoni.

Richard, as a way to possibly figure out how Zapparoni could have different appearances, begins to believe in the possibility that Zapparoni has hired actors or “shadows” or “projections” that would represent him in public while Zapparoni controlled and watched their actions. He even brings about the idea that Zapparoni invented robots in his own likeness and that Zapparoni could “enter apparatuses” and leave parts of himself “within them”, as to make the robots more in his image. For Richard who had grown up in a time where technology had not been this advanced, this seems like a plausible explanation to him and it shows how much society had technologically changed if something like being able to put your likeness in a machine is feasible. This also ties the story in with traditional science fiction topics of advanced technologies and androids (somewhat).

One thing that I find very interesting in the book that presents itself very heavily in this passage is the first-person narration of the story by Richard. The author does not simply describe Zapparoni’s appearance to us, but we are told about his appearance through Richard’s perspective. Everything that happens in this book is reflected and colored by the opinions, perspective, and worldview of Richard. Technically, we never really see and are never really described who the real Zapparoni is. We simply see the Zapparoni that is placed on a pedestal and filtered from the viewpoint of Richard.”

The arrival of spring in my junior year of college meant that it was time to register for classes in my senior year. Now entering my seventh semester of being an English major, I had grown weary of the literary canon; Shakespeare had been examined, the great poets had been dissected, and the classic novels had been close read. I came to the startling realization that now, at the end of my journey with English in an undergraduate context, I was falling out of love with reading – nothing was exciting me anymore.

Taking in the schedule of classes for the fall, something caught my eye… “Cold War Science Fictions.” They taught sci-fi in an academic context? Curiosity got the better of me, and I enrolled in the class. A few months passed, and into my e-mail inbox came the syllabus. My interest was piqued, to say the least. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Okay, the inspiration for Blade Runner…heard of it. The Dispossessed – I’ve at least heard of LeGuin. But….Glass Bees? Solaris? Roadside Picnic? What is all this stuff? Well, that’s what I get for something cross-listed with the German department, I guess. Nonetheless, I had a sense of excitement that I hadn’t really had in a while; sci-fi was my guilty pleasure, my hidden love, my shame as a scholar of “serious” literature. Nestled deep within that syllabus was a cheeky instruction to e-mail our professor what our favorite piece of science fiction media was, and I waxed poetic about my lifelong love of Star Wars, though I admitted I wasn’t exactly sure if it was “real” science fiction.

Our first reading assignment was not a novel, but a series of essays by science fiction scholars about the limits of the genre. I immediately came to realize that I was going to have my ideas challenged this semester; I became ashamed of my own shame about how much I loved sci-fi when I listened to the likes of Darko Suvin and Samuel Delany defend the genre. From its inception, I learned, sci-fi was viewed as a kind of pulp literature, something to be written off as dream-fodder for pimple-faced teens and untrustworthy adults. Suddenly, a lot of things, most especially my lifelong draw to science fiction, began to make sense. My whole life, I’d been written off for being “other.” I was a girl, girls can’t be Jedi for Halloween. Girls can’t be good writers. I was a lesbian. I was a little bit socially awkward. My shame turned to anger when I realized that a genre built by and for people like me, “othered” people, had been gatekept from me simply because some guy in a cardigan with a PhD in Chaucer said that anything with a spaceship in it isn’t “real” literature. And so my dedication to taking back what was mine began.

Not only did I voraciously read everything for class, but I started taking weekend trips to used bookstores and buying up things that interested me. When I walked up to the cashier with my arms full of Ray Bradbury and Frank Herbert, I actually felt a sense of pride. I was working hard both in and out of class, and I felt like a little girl plowing through books in my spare time yet again.

Admittedly, I did still harbor shame about some of my preconceived notions regarding my classmates; my guilt about liking things that weren’t “scholarly” manifested into assumptions that my peers would be girls with blue hair and guys who only wanted to derail our discussions to be about Star Trek. Actually, one of my classmates did have blue hair – and she was brilliant. And a lot of the guys were nerdy – but so was I! Studying English for so long had led me to a kind of academic island, such that I had been trained for so long to pick apart literature and write essays about my own ideas…did I know how to work collaboratively anymore?

One of our first written assignments was to do a close reading of a passage from Glass Bees – to my horror, we were split into groups, and were told that next class, we were going to meet up in these groups and create something that was a conglomeration of all of our ideas about the passage. I was in a group with only 3 other boys, and I hadn’t spoken much in class up to that point because I was very afraid of saying the wrong thing. When all was said and done though, the world didn’t end; Tony, Vinh, and Julian were actually very interested in my ideas, and I theirs.

Though this experience gave me a much-needed reality check about respecting my peers and myself, I was still terrified of speaking in front of the whole class. I never much liked the sound of my own voice, and I very much am afraid of judgment, so though I poured my heart and soul into my response posts for class, I mostly kept quiet. Then, our professor informed us that as a way of tracking our progress through the semester, we would need to set participation goals for ourselves and then self-assess them at the end of the semester. I decided this was the perfect opportunity to challenge myself, so I set a goal of making an effort to make some kind of contribution to every class…and I did.

The semester wore on, and I learned more and more about science fiction and its history, especially in a European Cold War context. It wasn’t really pulp at all, but rather was a means of encouraging young men all across the Soviet Union to pursue careers in STEM. In Europe, science fiction wasn’t a laughingstock at all – it was a serious and important means of self-expression, and even a kind of service to the government.

As the semester neared its closed, we began one of our last novels: The Dispossessed by Ursula K. LeGuin. This novel awakened something in me. LeGuin wrote like she wasn’t afraid of what anyone had to say about her work; she wrote fearlessly and with no regard for what was “right” or “wrong” with regard to either the genre or the conventions of literature. This novel puts out the question of what perfection means, and if it’s even really possible, and the best part is the fact that LeGuin herself doesn’t propose to know.

I’ve come to understand, both frustratingly and excitingly, that science fiction is not the literature of answers, but of questions. Sci-fi asks “what if?,” but doesn’t set out to answer it. The spirit of the genre is exploration and discovery. Authors create universes for readers to explore, and there is no right or wrong way for this interaction to happen.

I think I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge that my time in Cold War Science Fictions occurred with a backdrop of a global pandemic. Having to learn remotely creates a real barrier to learning, but as a class, we conquered this obstacle together. In the scariest, most isolating time of my life, science fiction found me, and I don’t think this was a coincidence. At a time where the only place I went besides my own house was the grocery store, a world of opportunity spread out before me – many worlds, in fact. This semester, I met an eccentric and mysterious toymaker, bounty hunted androids, made contact with a sentient ocean, scored swag from the Zone, shared the secrets of time and space with the entire universe, and played vlet. And I didn’t even have to leave my house.

I’m hesitant to close out this small story that is serving to introduce my ideas with thank yous, as if done wrong they reek of hollow kissassery, but I’m going to do so anyway. To my peers: thank you for challenging me every class, and for encouraging me to speak up about my own ideas. You are all brilliant in your own unique ways, and I have found great joy and comfort in learning alongside you. To my professor, Carl Gelderloos: your mastery of a genre we have all grown to love is unmatched, but more importantly, in a time where nothing felt stable, your empathy and warmth were a constant. You taught me so much about a subject I now have grown to love so deeply, but also showed me such great kindness when I stumbled in the face of adversity. We are all better for having known and learned from you. Lastly, to authors and readers of science fiction both near and far, thank you. Without the bravery of authors in the face of criticism and ridicule, there would be no body of work for us to study. And without people to care about that writing, to read it, to care about it, to discuss it, there would be no point in writing it.

My journey this semester was about science fiction, but it really was more than that. The genre of discovery brought me on a journey of self-discovery, and on the pages that follow here are the ideas it gave to me.